Is ‘mental health’ a cross-cultural category? A key debate yet to be had

By Erick Nascimento Vidal ~

The Layton Dialogue is in the nature of an experiment: two scholars are invited to speak on the same topic to see how their ideas might interact. It seems appropriate, then, that last year’s edition of the event took place in honour not only of the remarkable anthropologist it is named after (Robert Layton), but also of Gregory Bateson, who made the question – ‘How do ideas interact?’ – his own. Moreover, the topic being ‘mental health’, Bateson’s trajectory through social anthropology, psychiatry and evolutionary biology was bound to prove an inspiration. Finally, Durham University’s Department of Anthropology – with its parallel emphasis on evolutionary and social anthropology, as well as its institutional distinction between social and medical anthropology – was set to be an excellent environment. Indeed, the experiment might be seen as a test of under what conditions such distinctions, parallels and dialogues can be fruitful.

An implicit lesson is perhaps that such fruitfulness hinges on both conceptual and comparative questions. The first speaker, for instance, talked freely of ‘God’, other ‘gods’, and ‘spirits’ in a number of regions of the world (the USA, Ghana, India), in connection with voice-hearing, without questioning the implications of that vocabulary. Nevertheless, the talk did finish by effectively re-framing the problem in more abstract terms: ways of dealing with passages and relations between what is experienced as coming from inside or outside the person. It would have been important, with additional time, to follow more closely how this analytical move is made; that is, how comparability is analytically achieved, after having been provisionally assumed. Are the presumably different notions of personhood, ontology or expression which underlie these phenomena in such distant places somehow neutralised in the work of analysis? Are they perhaps synthesised as variants at a more general level? Such questions remained open during the debate.

The second speaker, more sceptically, questioned the category of depression throughout, but finished by pointing out how the multiplicity of ways of scientifically segmenting reality (for instance, the various types of social and biological context which can and have been shown to impact mental health) impinges on the discussion. It would be important, in this case, to ask how these perspectives might be articulated, or perhaps alternated, in an approach to complex phenomena as such – a Batesonian question which foreshadows some of Marilyn Strathern’s work. A matter, in both talks, of the nature, the mechanism, and the effects of certain boundaries: those established by science as well as those implied by other forms of practical speculation.

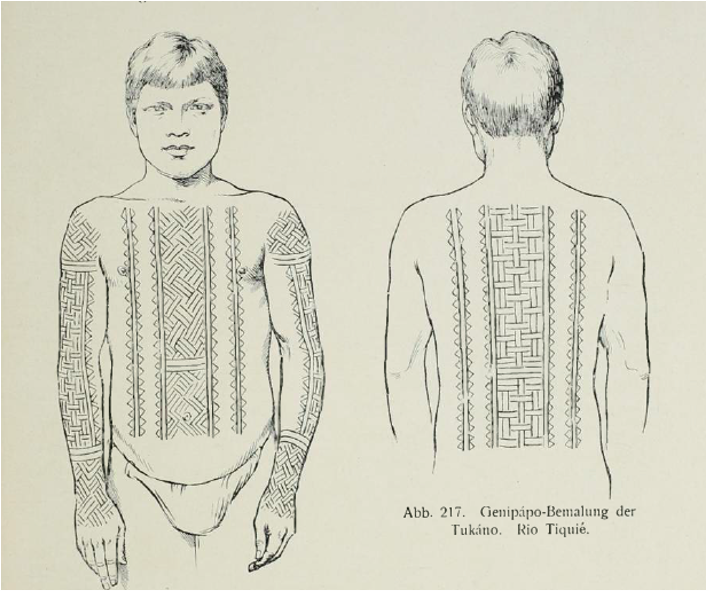

Consider, for contrast, the image above, by Theodor Koch-Grünberg (1909). In indigenous Amazonia, basket-woven surfaces are connected to the control of certain flows (of poisonous liquids during food-production, of flour, of other foods, of light, of graphic motifs…), thus also mediating between the inside and the outside of various kinds of spaces and, indeed, bodies. They are presumably connected, then, to notions of a well-balanced, healthy and joyous life. Much the same goes for body-painting, skins and layers being a major cosmological topic – so that painting surfaces with basketry patterns can be particularly evocative. Northwest Amazonians even paint shamans’ benches with such designs, as if the work of cosmological mediation they perform depend on controlling the porosity of their own bodies. Would these have been an apt terms of comparison for the discussions that took place during the Layton Dialogue?

Such comparative problems are not new. In fact, a direct comparison of religious experience (in the Western sense), schizophrenia (or depression, for that matter), and the cosmological notions and experiences of non-Western populations, might have evoked Freud’s Totem and taboo (1913), with its irksome subtitle, strongly reminiscent of Victorian anthropology: ‘some agreements between the mental lives of savages and neurotics’. Unsurprisingly, Freud’s book was discussed in the past by such anthropologists as Alfred Louis Kroeber and Claude Lévi-Strauss, who were touched not only by the questionable path of the implied comparison, but also by the relevance of Freud’s insights in his strictly psychoanalytic works. The relationship between these two dimensions (the comparative and the clinical) proved a productive topic.

Thus, Lévi-Strauss, who often followed unexpected paths in pairing Western philosophical and scientific ideas or procedures with non-Western ones present in myth and other practices – holding both sides as equally complex – at one time also compared Amerindian shamanism and psychoanalytic therapy explicitly. He mostly tried to show on what level such a comparison was possible between something that works for many Westerners and something that reportedly works for Amerindians – and what it might reveal about both.

Whether Lévi-Strauss’ discussion seems satisfactory today is up for debate, of course. Still, it would be interesting to know what anthropologists nowadays – especially those working on such things as schizophrenia and depression – might themselves make of the sort of ethical, comparative and conceptual problem which works like Freud’s Totem and taboo can represent.

As it happens, though, despite a century of intense debate, revision and re-elaboration, psychoanalytic literature has been largely ignored in contemporary anthropology. It is also ignored in contemporary debates about ‘mental health’ in the UK. Consider a recent edition of The economist: while a point is made that increased ‘awareness’ of mental health issues often slips into over-diagnosis of normal responses to life-situations, with a tendency ‘to medicalise problems unnecessarily’, no real intermediary appears between psychiatric intervention (in more acute disorders) and, so to say, nothing… Yet, that wide gap is likely where most people’s common lives (arguably the primary subject of social anthropology) happen.

It is here that the absence of (Freudian or other) psychoanalysis becomes harmful. After all, whatever the shortcomings of its first formulations (especially its attempts to go beyond Western experience, where ‘mental health’ is not necessarily a given category or does not necessarily have an easily recognisable equivalent), this is perhaps the approach to psychotherapy which most radically frames treatment as the fundamental restructuring of the symbolic framework of one’s subjective and relational experience – an eminently anthropological topic. Yet, prevailing silence at a time when, in the West itself, the meaning of ‘mental health’ is being disputed, means that the comparative problems implied by psychoanalysis as an approach to human life remain unaddressed and its major (conceptual and practical) contributions ignored.

Without going into the maze of critical social theories which have in the past engaged with psychoanalytic literature – still a hot topic in certain other countries – inspiration can be found within social anthropology itself: for instance, in notes by the always insightful Hocart, or in one of Malinowski’s classic, polemicising books. More to the point, Bateson’s own comments on Freud provide an interesting, methodologically provocative start.

Erick is a PhD student in Social Anthropology at Durham University, currently working on relations between three settings of Northwest Amazonian basketry: traditional modes of livelihood, urban trade and indigenous schooling.

Further Reading

Bateson G (1972) Steps to an ecology of mind. New York: Ballantine Books. See comment on Freud on p. 58 of this edition; the question, ‘How do ideas interact?’, is on p. 21.

Strathern M (1991) Partial connections. Walnut Creek: Altamira Press.

Hocart AM (1925a) Psycho-analysis and anthropology, Man, 25, 24-25.

Hocart AM (1925b) Psycho-analysis or anthropology, Man, 25, 183-184.

Kroeber AL (1920) Totem and taboo: an ethnologic psychoanalysis, American Anthropologist, 22, 48-55.

Kroeber AL (1939) Totem and taboo in retrospect, American Journal of Sociology, 45, 446-451.

Lévi-Strauss C (1949a) Les structures élémentaires de la parenté. Paris : Mouton. Final chapter.

Lévi-Strauss C (1949b) Le sorcier et sa magie. In Anthropologie structurale. Paris: Plon. On shamanism and psychoanalysis.

Lévi-Strauss C (1962) Le totémisme aujourdh’ui. Paris : Plon.

Malinowski B (1927) Sex and repression in savage society. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Ingold T (ed. 1996) Key debates in anthropology. London: Routledge.

1 Comments

zoritoler imol